Works by Anton Kohalyk

I found this collection of paintings by Anton Kohalyk at a rummage sale at senior’s centre in Edmonton in 2024.

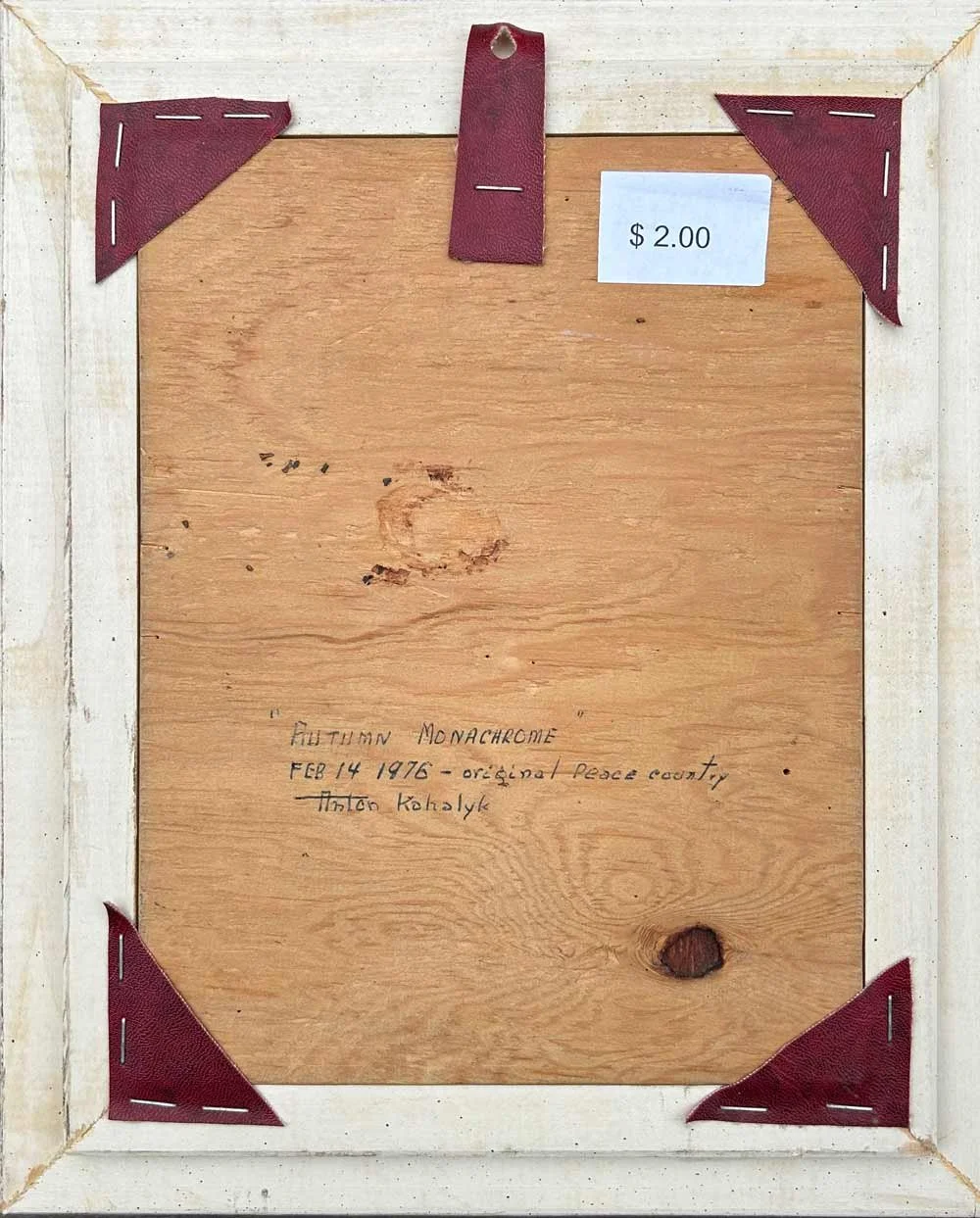

Autumn Monochrome

Feb 14 1976 - original Peace Country

Anton Kohalyk

Paint on wood panel

6.5” x 8.5”

Back of Autumn Monochrome by

Anton Kohalyk

Birch by the Slough

May 9, 1976

Anton Kohalyk

Paint on wood panel

Back of Birch by the Slough by Anton Kohalyk

Gold Creek

Feb 21 1976

Anton Kohalyk

Paint on wood panel

5.5” x 6.5”

Back of Gold Creek, by Anton Kohalyk

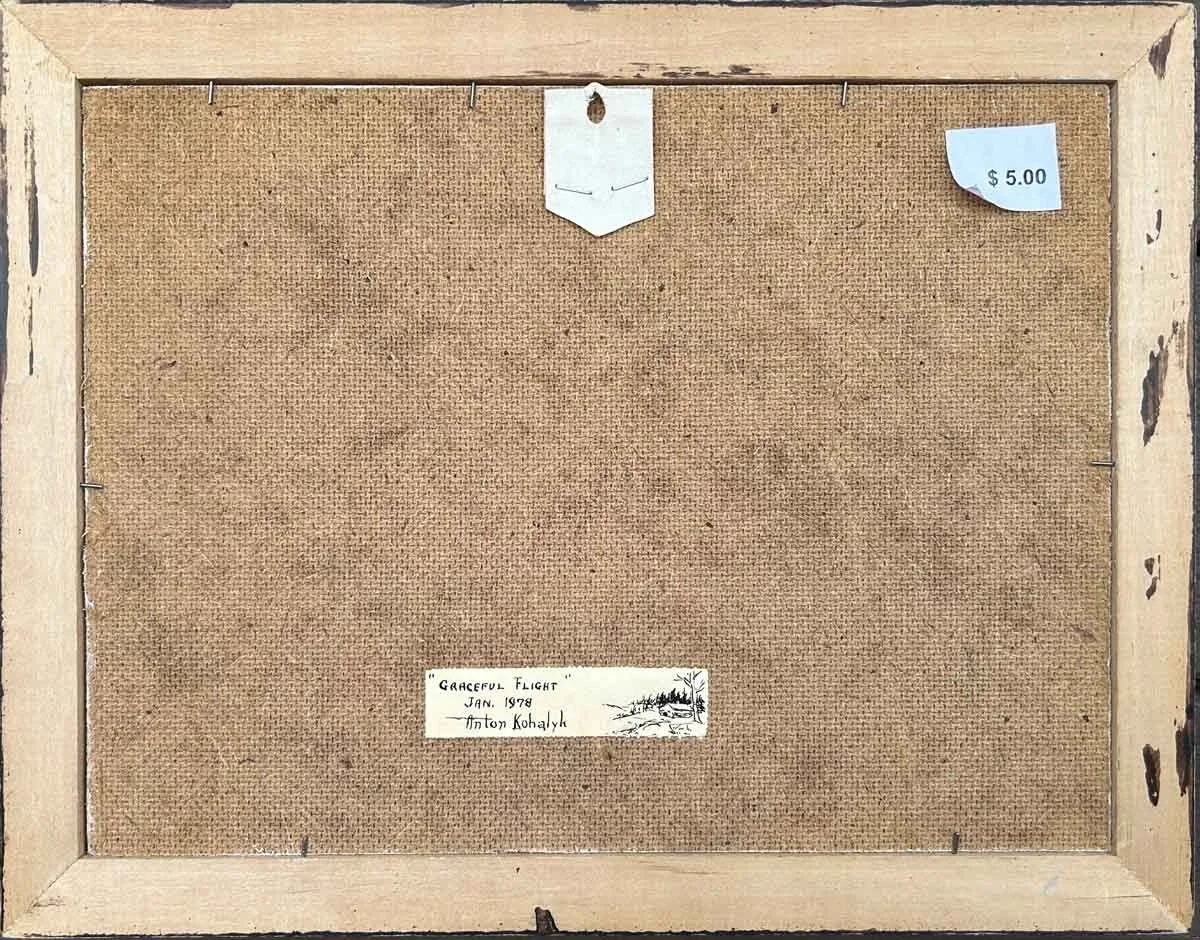

Graceful Flight

Jan 1978

Anton Kohalyk

10.5” x 7.5”

Paint on wood panel

Back of Graceful Flight by Anton Kohalyk

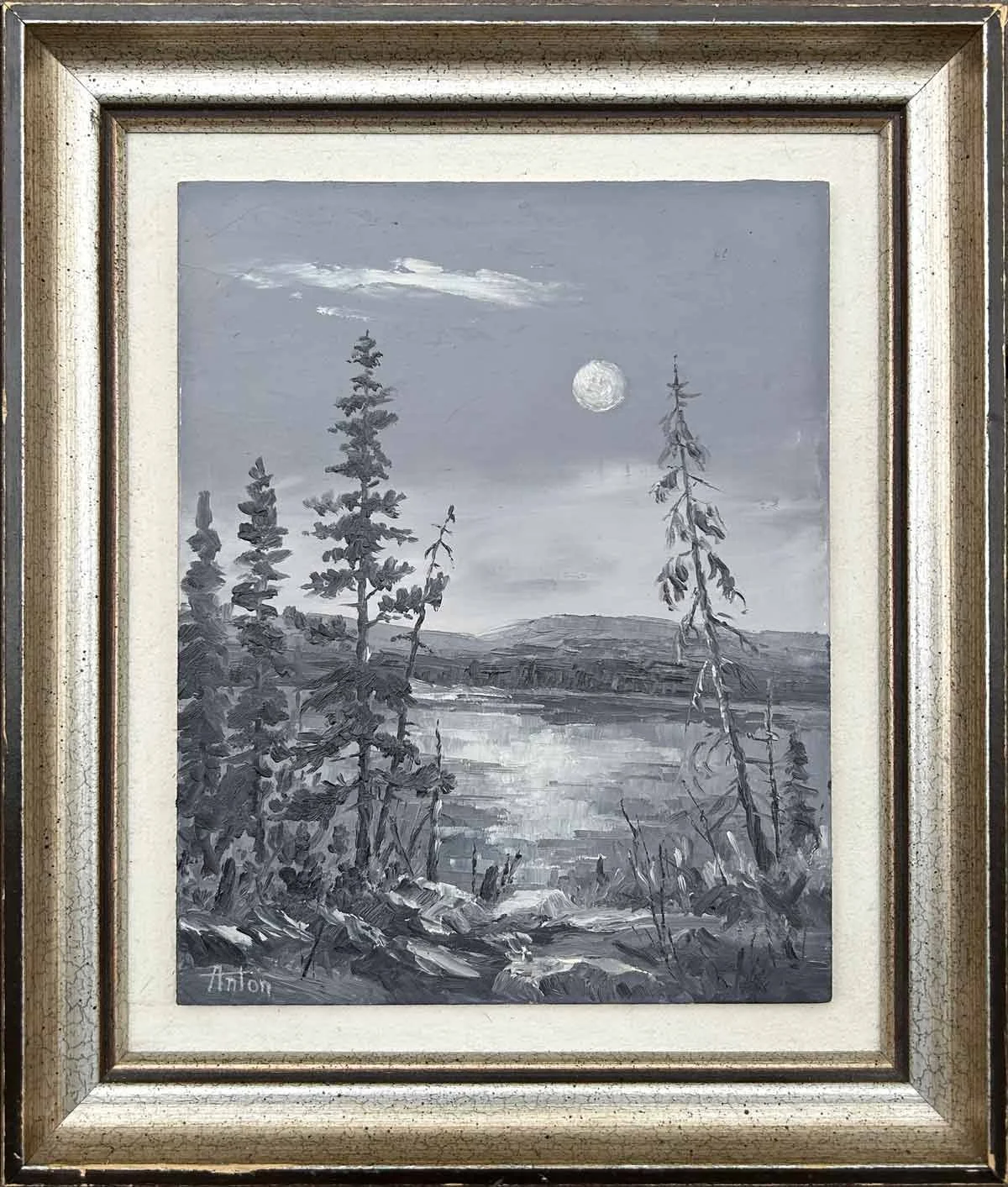

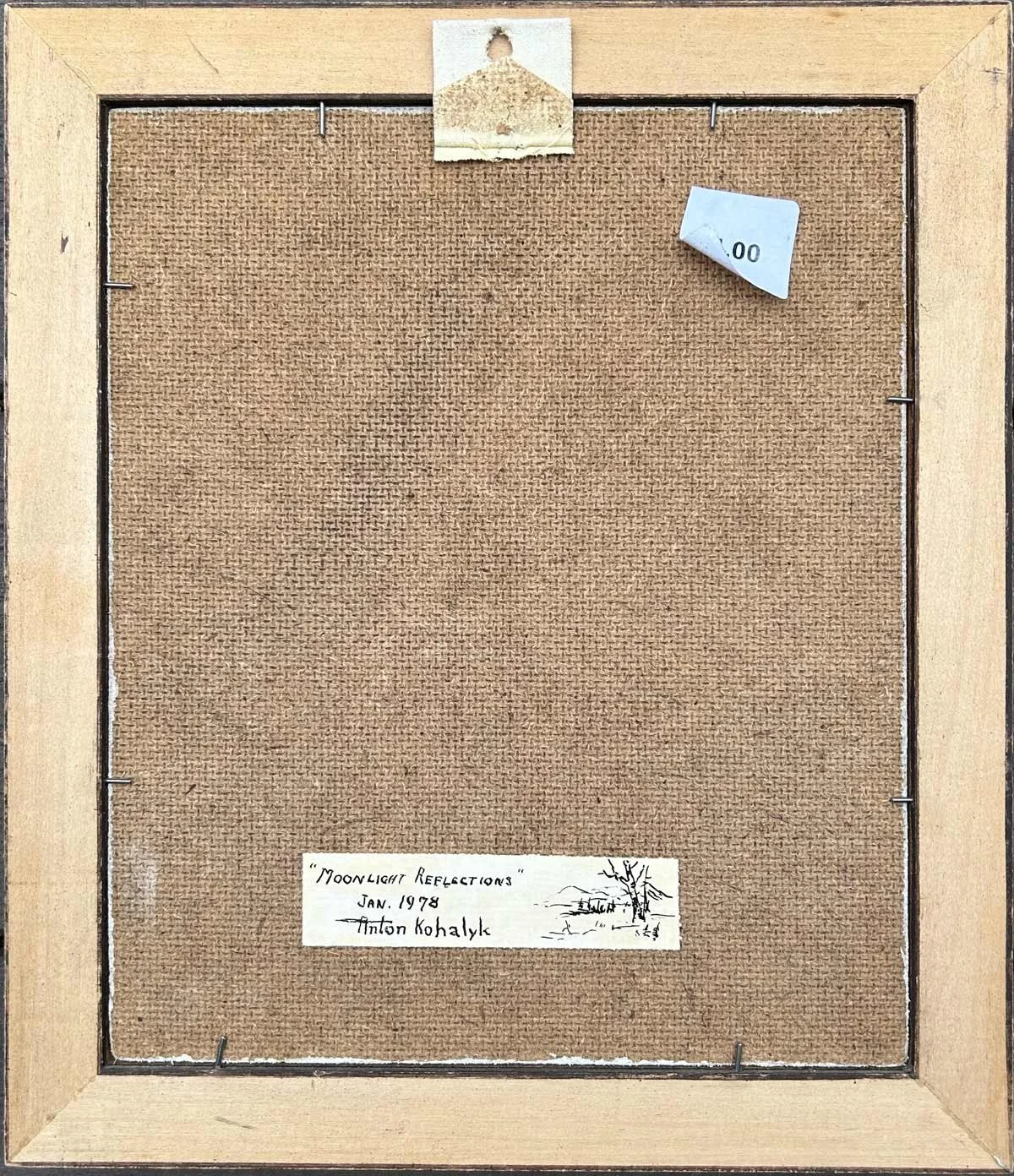

Midnight Reflections

Jan 1978

Anton Kohalyk

Paint on wood panel

7 3/8” x 9”

Back of Midnight Reflections by Anton Kohalyk

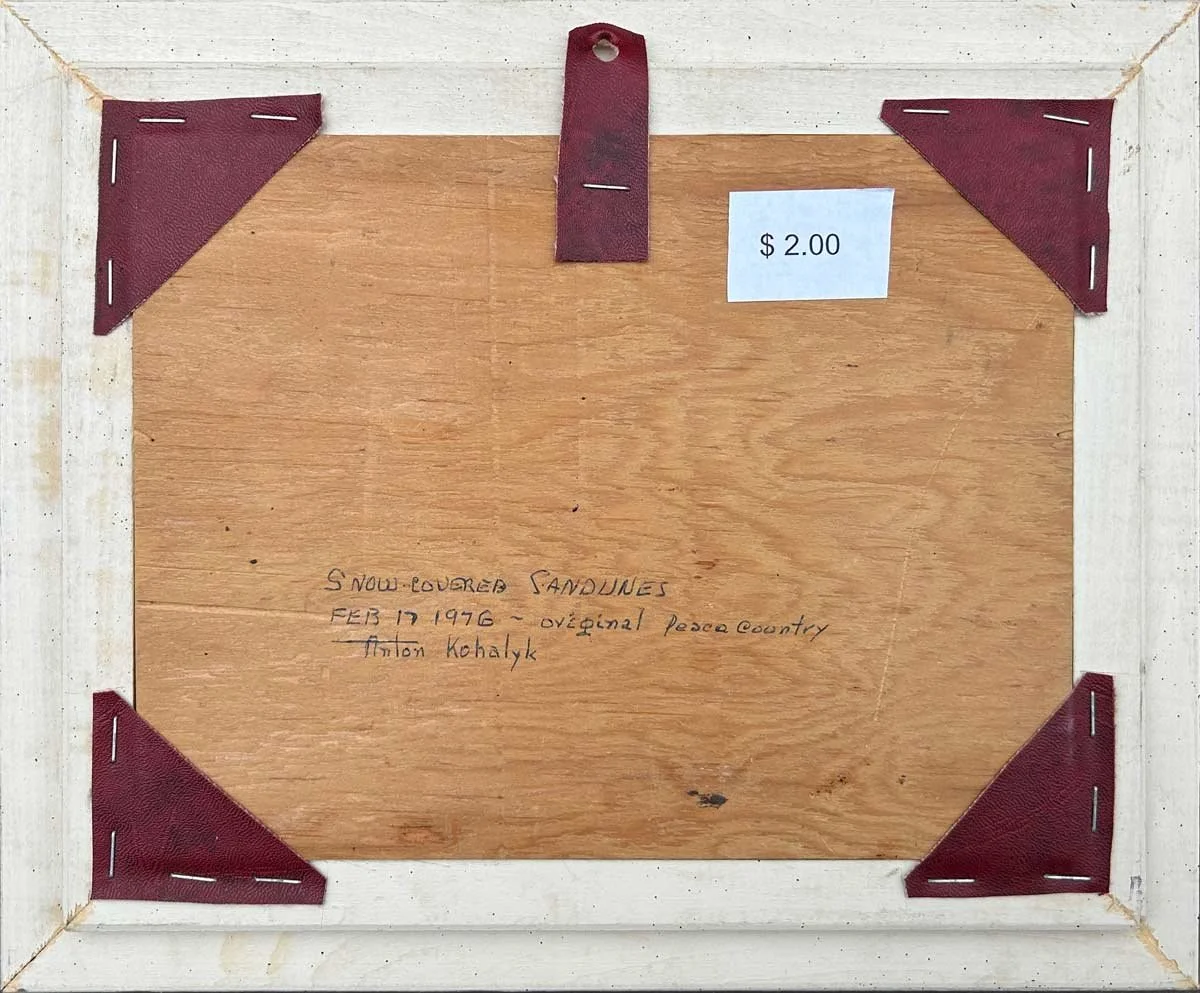

Snow Covered Sandunes

Feb 17 1976 - original Peace Country

Anton Kohalyk

Paint on wood panel

8.5” x 6.5”

Back of Snow Covered Sandunes by Anton Kohalyk

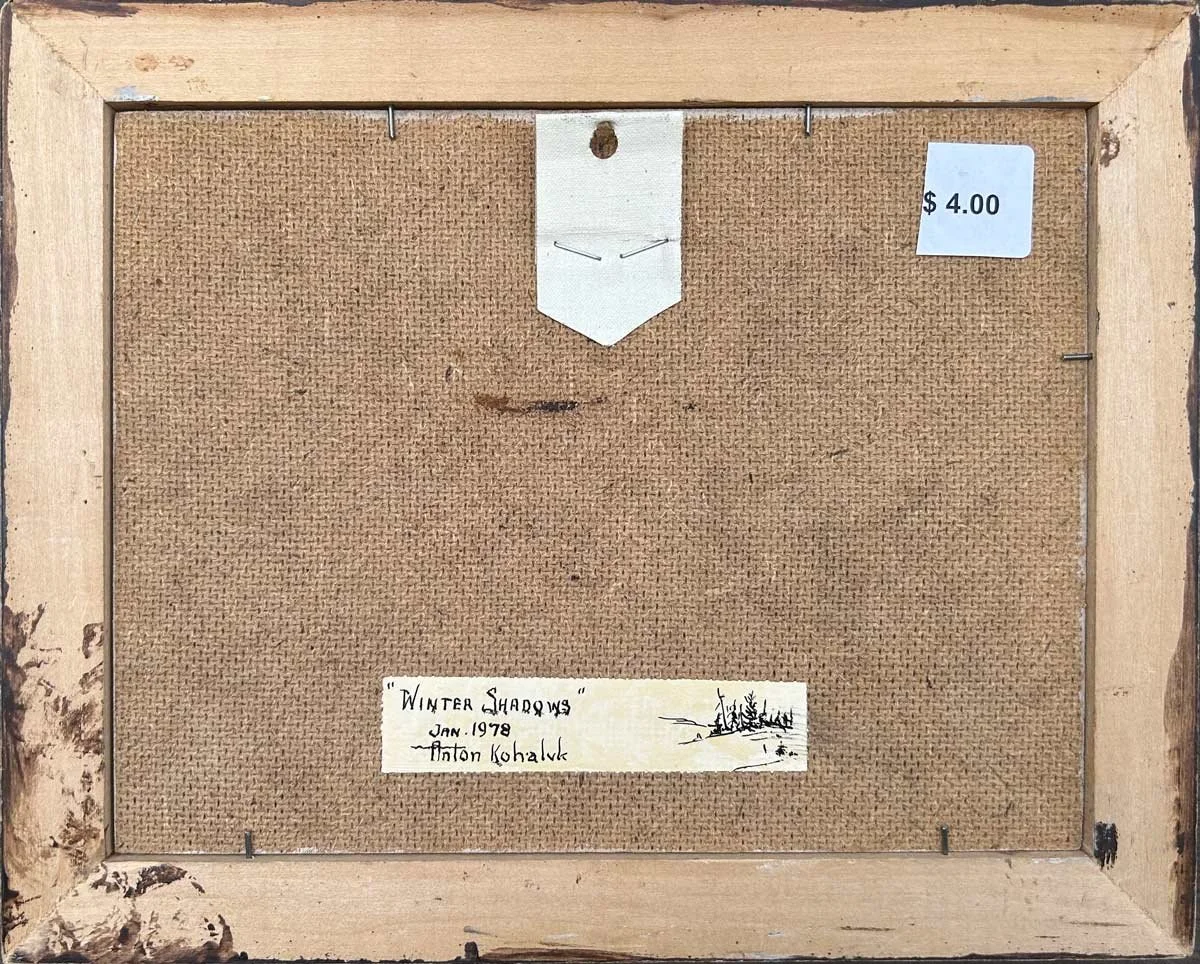

Winter Shadows

Jan 1978

Anton Kohalyk

Paint on wood panel

8.5” x 6.5”

Back of Winter Shadows by Anton Kohalyk

This group of paintings by Anton Kohalyk reads less like a collection of individual works and more like a sustained meditation on place. Seen together, they reveal an artist returning to the same terrain again and again—listening, adjusting, refining—until the land speaks back in his own restrained, unmistakable voice.

Kohalyk lived in the Grande Prairie area from 1934 onward, and these works feel inseparable from that long familiarity. Forest edges, frozen sloughs, snow-laden trails, moonlit clearings, and quiet waterways recur throughout the series. Even when animals appear—most strikingly in the painting with geese lifting into flight—they do so without drama. They belong to the land rather than interrupt it.

What immediately binds these paintings together is their monochromatic restraint. Kohalyk was known for his unusual and subdued use of colour, especially whites, and this group exemplifies that reputation. Snow is never a single tone: it shifts between grey, taupe, blue, and warm earth notes, built up with confident palette-knife strokes. Trees are rendered not as delicate botanical studies but as structural forms—birch trunks flashing pale against darker masses, conifers dissolving into rhythmic verticals.

Although clearly representational, none of these works feel photographic. Paths curve gently rather than precisely. Forests compress and open according to feeling rather than strict perspective. The moon becomes a simple, luminous disc. These are remembered landscapes as much as observed ones—places filtered through time, repetition, and touch.

Kohalyk’s working method matters here. He often painted directly from the land rather than from photographs, and he preferred the difficulty of the palette knife over the control of the brush. That choice shows in the surfaces: thick, sincere, and quietly physical. Even in their modest scale, the paintings hold presence. They ask the viewer to slow down, to notice tonal shifts, to sit with the quiet.

There is also a notable humility in this work. Kohalyk was not interested in trends, art-world debates, or spectacle. As he once said, he wanted “feeling” in his paintings—something absent from what he described as “run-of-the-mill” art. These works embody that conviction. They depict what many would pass by every day, yet they do so with care, dignity, and attention.

Seen together, this series feels like a visual archive of the Peace Country as lived rather than idealized. These are not heroic landscapes or romantic wilderness scenes. They are places known through repetition: walked, watched, revisited across seasons and years. In that way, Kohalyk’s paintings function as quiet acts of stewardship—records of looking closely and valuing what is already there.

For a collector, this group offers something rare: not just seven paintings, but a coherent, deeply rooted body of work by an artist who painted for the land itself, and for those willing to look a little longer.